Mallory was feeling sorry for me. She had won four or five races in a row. She suggested that I get a head start to give me a chance at victory. We were running for the red truck about 60 yards down the street. Mallory is 8, and the granddaughter of my sister Colleen, who said she just knew I was going to get hurt, because “you always get hurt.”

When the race started, I tried to hit a gear that I shouldn’t have reached for. It was as if I blew out a tire as I hit the asphalt, breaking my fall with my hands and taking down Mallory with me. Thankfully, she wasn’t hurt. I tore my left hamstring.

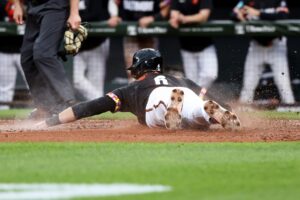

I was reminded of it nearly two weeks ago when Ryan Mountcastle stole home on a double steal for the Orioles, who stole a 2-1 win over the White Sox. Mountcastle’s was the deciding run. He paid a price, suffering a severe hamstring injury that will keep him out eight-to-12 weeks.

On Tuesday, Cedric Mullins and Jordan Westburg, both of whom landed on the injured list because of strained hamstring muscles, were reinstated by the Orioles. Westburg, who has hit home runs in his first two games back, will share time at third base with Ramón Urías, who also hit a home run in Wednesday night’s 10-1 win over the Tigers and was out with a hamstring injury earlier this season.

Baseball is a difficult sport for a number of reasons. It requires exceptional hand-eye coordination, reflexes and split-second decisions on whether a pitch is a fastball, changeup, splitter or breaking ball. Batters can look foolish, with high-definition TV making those choices look far easier than they are. It’s also dangerous. Colton Cowser swung at a fastball up and in during the playoffs, striking out and breaking his hand in the process. He thought the pitch that hit him was a breaking ball.

Baseball also requires a lot of standing around while waiting for something to happen when, suddenly, a third baseman is diving for a rocket or an outfielder takes off on an all-out sprint to catch a ball headed toward the fence.

Baserunners are trying to beat out infield grounders or, in the case of Mountcastle, making a daring dash for home. He’s 6 feet 3, 220 pounds, and runs well. On the double steal, he wanted to run faster and put too much tension on the right hamstring muscle.

Hamstring muscles, which run from the top of the back of the leg to just below the knee, are highly susceptible to injury, especially in athletes who run and sprint, stop suddenly or change direction.

Hamstring injuries primarily occur when there is extreme stress on the muscles. It can happen while sprinting because the hamstring muscles must bear the body’s weight and experience heavy contraction when one pushes off the ground to move forward. They’re also challenging to strengthen.

I’m not off the injured list, but I’m working on it. I reinjured my hamstring after returning to running this past winter. I’m getting physical therapy from Cathy Latoof, who continues to help me heal from various injuries, which my sister, Colleen, pointed out in a recent conversation. “You always say you won’t run again, and then you come back. I hurt my leg, and I thought of you.” In effect, she was saying that my negativity helped her remain positive, and she is doing better.

On Tuesday morning, when I was getting treatment, another patient said this when we brought up Mountcastle and the amount of hamstring injuries to baseball players. “That’s because they’re standing around, and then they’re going all out.” In other words, they’re trying to go from 0 to 60 too quickly for their motor muscles to meet the demand.

I don’t have the need for speed, but I am determined to keep running. Like Westburg, Mullins, Urías and now Mountcastle, I’ll keep working to get back on the field, or in my case, back on the trail. It’s good to know that I’m in the company of such superb athletes, at least when it comes to hamstring issues.

And, no, I haven’t scheduled a rematch with Mallory.