Summer is almost here, and the bugs are arriving, too: The warmer weather has brought new concerns about midges, ticks and much-disdained spotted lanternflies. Here’s what to know about possible health hazards, environmental threats and impacts to communities from these insects across the Baltimore region.

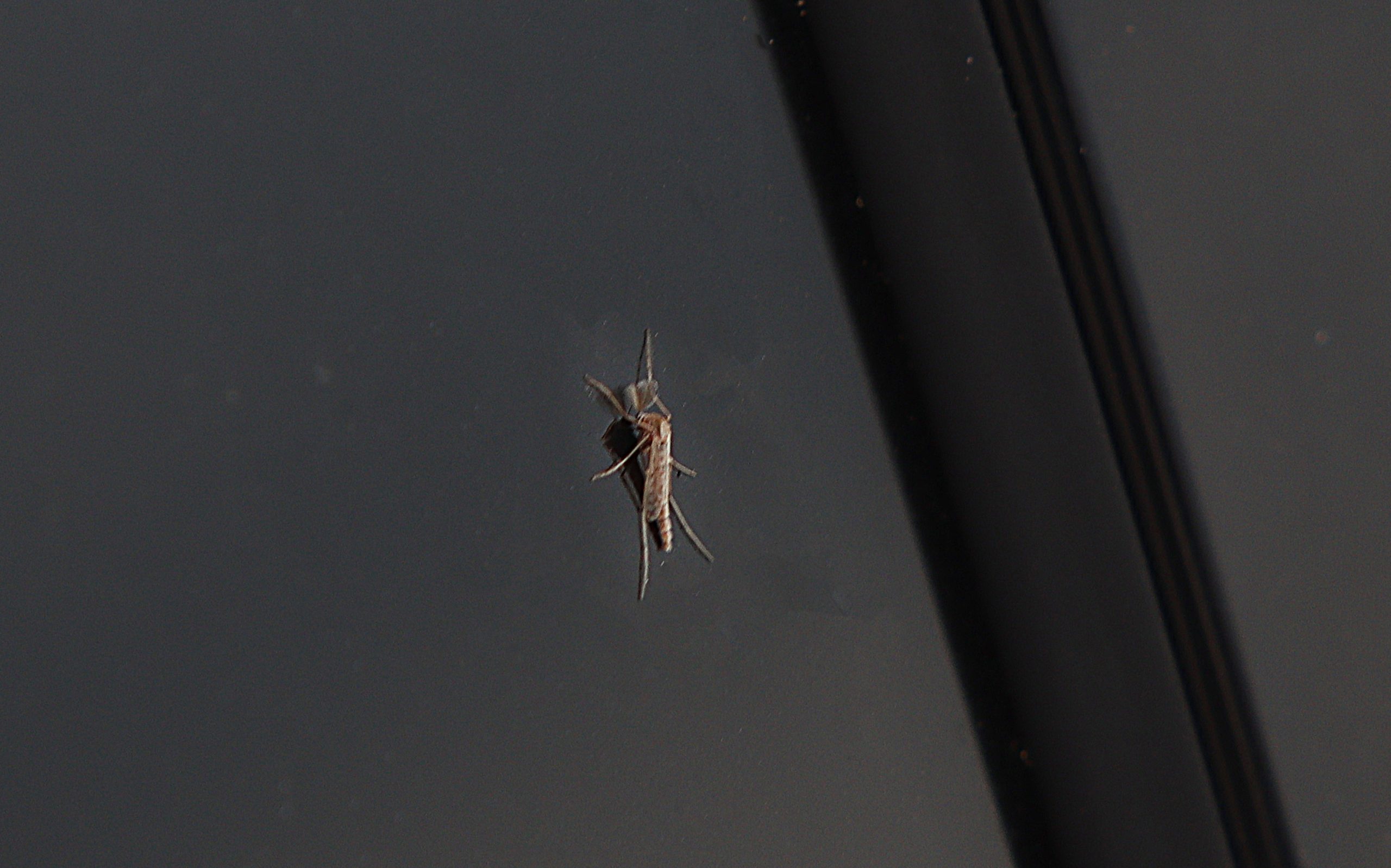

Midge infestation

In recent weeks, Baltimore County has witnessed an aggressive surge in the midge population, with infestations forming near bodies of water and reports along Back River up to Bird River. Residents have described intolerable levels of midge populations as thick swarms form around residents’ homes, cars and even hospitals, according to reports in the Baltimore County Environmental Reporter, which tracks midge sightings.

The good news is that midges, despite being an extreme nuisance, pose no physical or health threat. This new species of midges is not known to bite or to be a disease vector, according to Kevin Brittingham, the manager of Baltimore County Department of Environmental Protection & Sustainability’s Watershed Monitoring Program, who spoke on a community briefing held by County Councilman David Marks on May 29.

So why is this season seeing such a drastic increase in population?

“There’s no definite answers, but we definitely know that we’ve had a lot of rain this year … which has drastically reduced the salinities in our creeks and rivers,” Brittingham said on the recorded Zoom briefing.

And as more freshwater comes in through rainfall, alongside weeks of unseasonably cool temperatures, creeks and rivers are offering the perfect conditions for midges to thrive.

New initiatives are being employed to combat the infestation, such as increasing the monitoring of larvae midge populations to the entirety of Back River, or an additional 3,200 acres of river, according to an email sent by Horacio Tablada, Maryland’s secretary of the environment.

Still, it does not appear that the bugs are set to subside anytime soon. But in the meantime, there are a few things you can do to curb their effect.

Limiting outdoor lighting, using yellow light bulbs and closing your shades at night can help keep the midges at bay, according to Tablada, who also spoke on the Zoom briefing.

Ticks are carrying a new disease, called babesiosis

Babesiosis, a tick-borne illness, is making its way to Maryland after historically being limited to regions in the Northeast, according to a research paper published in April by the Journal of Medical Entomology.

Babesiosis, while still rare, is most commonly spread through bites from deer ticks. Maryland’s Eastern Shore and the Baltimore region are hot spots for ticks carrying the disease, accounting for 55.5% of the reported cases in Maryland from 2018 to 2022, according to the research report.

Like other tick-borne illness, effective treatments exist to combat babesiosis, but if health care providers aren’t used to looking for the disease, it could be easy to miss. Left untreated, babesiosis could be fatal, especially in more vulnerable populations, such as older adults and those with weakened immune systems.

Although those with babesiosis do not always display symptoms, common effects of the disease are fever, chills, sweating, body aches, appetite loss, nausea and fatigue.

Still, Lyme disease, also carried by ticks, is far more prevalent throughout Maryland, with 2,463 probable cases in 2023 according to data from the Maryland Department of Health, compared with babesiosis’s 23 reported cases. Although both diseases can display similar symptoms, they are treated differently. Antibiotics used to treat Lyme disease are not sufficient for dealing with babesiosis, according to the research paper.

To prevent contracting or spreading either Lyme or babesiosis, make sure to wear a long shirt and pants while venturing into wooded or grassy areas. If you find a tick on yourself, quickly remove it with tweezers and save it in a container to show a health care provider.

Lanternflies are returning, but there’s hope for their decline

A new generation of the spotted lanternflies, an invasive species originally native to China but present in the United States for nearly a decade, are already appearing across Baltimore County. The leaf-hopping insects first appeared in Maryland in 2018, and since then, their population has grown with incredible speed.

Although lanternflies are not known to bite or be vectors of diseases, they do cause immense harm to their surrounding environments, according to Michael Raupp, an entomologist at the University of Maryland, College Park.

The spotted lanternflies cause “severe damage to vineyards, and this where they are a major, direct problem,” Raupp told The Baltimore Sun. The bugs’ tendency to feed on plants can lead to a decrease in yields and stunt a crop’s growth.

In addition, spotted lanternflies excrete a sweet sap called honeydew that can draw stinging insects, such as bees or wasps, to residential areas.

Throughout the Baltimore region, spotted lanternflies are expected to return in full force this season, Raupp says. But northern counties in Maryland, which were the first to witness the lanternfly invasion, offer some hope that Mother Nature might be able to fight against the harmful insects.

“In some areas along [Maryland’s] northern border, where we border Pennsylvania, we’re beginning to see reductions in the population,” Raupp noted. “Back at ground zero, in Berks County, [Pennsylvania], and other areas in central and southeastern Pennsylvania, the populations have declined dramatically.”

Raupp attributed this decline to what he said was Mother Nature “waging war on spotted lanternflies,” as different species of birds and invertebrates, such as praying mantises, discover and consume the invasive insect. Raupp noted that “eventually these forces will enact” throughout the Baltimore region, but it could take three to five years.

In the meantime, a variety of methods can be employed to combat lanternfly infestations, from pesticides to destroying egg masses.

Have a news tip? Contact Hannah Epstein at hepstein@baltsun.com.